We’re going to assume here that things have gone sideways, for you and everyone else in a 300 mile radius, and you aren’t expecting a righting of the ship anytime in the near future. Maybe a solar storm or EMP took out the grid, or the dollar finally took a dive and the safest place to be is away from people.

Whatever the case, we’re assuming it’s a worst case SHTF, dust-isn’t-settling-anytime-soon kind of scenario, and you plan on being away for weeks , if not indefinitely.

We’re also assuming that you are heading out prepared and not just wandering out willy nilly with a fanny pack full of snacks and some bottled water hoping to “live off the land”.

Your bug-out bag might be enough to keep you going for a few days, but in our scenario we are looking at weeks to months time spent away from modern civilization. Your INCH (I’m Never Coming Home) bag is what you’ll need for an extended emergency bug-out.

Expanding upon the concept of the INCH bag, think about the things you would need to spend weeks or months away from home with. Food, Water, and Shelter will be covered below, but consider your varying individual wants and necessities.

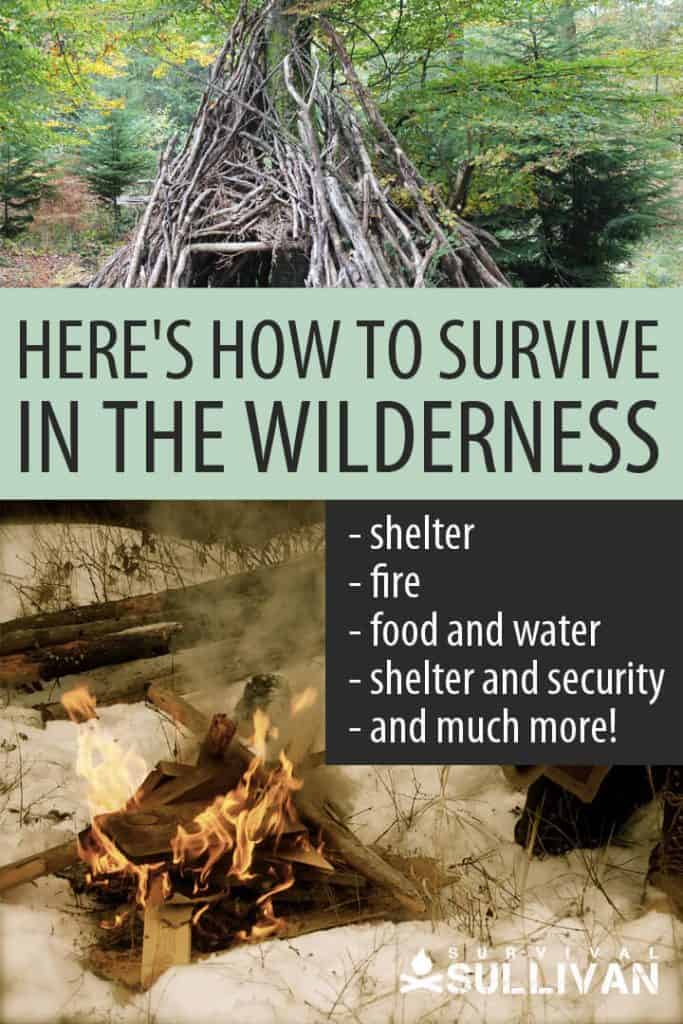

In what follows, we’re going to cover everything related to how to survive in the wild and we’re going to link to relevant articles that go in-depth on each topic.

And let’s start with the four most important pillars of any survival situation, namely:

If you can take care of these four pillars, you should be all set for surviving in the wild for a very, very long time.

Table of Contents

Regardless of your situation, the survival rule of threes teaches us that the #1 most important thing in a wilderness survival situation is shelter. You read that right, it’s not food or water, it is shelter and staying warm.

Because hypothermia can be a quick and merciless killer in the wild. Whether the night approaches or if you’re soaking wet for whatever reason, you need to get dry ASAP and to find a place to keep warm for the night.

Of course, choosing a campsite is very important.

Whether you are making camp for the night or for the long term, finding the right location is key. Choose a level location, naturally sheltered from the wind or from other elements if possible.

Always make camp at least 300 yards from from water, further if near a river or spring. You want to be clear of any rising water in a flood as well as animals headed to drink.

You don’t want to make camp right on a common trail or road for numerous reasons. Spend the extra time to scout out a good location, and always try to set up camp with ample daylight left. You don’t want to wake up to any surprises.

There is a primitive comfort in having a fire. You will need it for cooking, sanitizing, and warmth.

If you are planning to camp in a location for longer periods you can keep your coals going and bring the fire back to life when you need it. If you are breaking camp, extinguish your fire completely.

Your fire is your responsibility in nature and you must tend it! A careless wildfire will not just wreck the forest, but also you and anything else in its path.

In your INCH bag you should have 3-5 bic lighters, waterproof matches, and some type of fire tool, and a source of tinder at all times.

Some articles recommend learning the bow drill method, but the chances of getting it to work in a real life survival scenario with wet or the wrong kind of wood are very slim… not to mention you’ll exhaust yourself instead of keeping your strength. There are other ways to start a fire.

Wool socks are a good investment. Wet feet never helped anyone, and it can affect your health. In general you don’t want to get wet unless you will have ample warmth and sun to dry you.

In cold weather hypothermia is a serious concern for your extremities especially. Staying warm and dry is a main goal for your comfort and health.

There are many lightweight backpacking tents available that weigh 1lb. or less. Having a lightweight tent that is easy to setup and teardown will keep your camp mobile when necessary.

When it comes to long hiking trips, every ounce you can shave off your pack will make a difference.

You want a 3 to 4 season tent with a waterproof floor that has room for you and all of your gear. Pick a somewhat flat or neutral color to blend in a bit more with your surroundings.

Disclosure: This post has links to 3rd party websites, so I may get a commission if you buy through those links. Survival Sullivan is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. See my full disclosure for more.

You want a tent that can be firmly anchored, and is adjustable to your climate. 4 season tents are warmer and typically made with bad weather in mind, while in warm climates mesh ventilation from 3 season tents will be another thing to consider.

You want to balance durability, practicality, and weight to get the best option with the least work to setup. There are even models with inflatable support beams.

A rain fly and tarp for under the tent is a must. I pack a few weather tarps when heading into the back-country, one to lay on and the other for cover in a pinch.

A good sleeping bag is included in shelter, and don’t be afraid to shell out good money for one of these. A good down bag, rated for 15 degree weather at the minimum, that can compress down pretty small is what I recommend.

Sleeping pads are a good investment, and don’t take too much room in your pack. Sleeping off the ground is key to staying warm in cold weather.

Although making your own shelter in the wild is something you may not need if you have a tent, it’s still good to know. Maybe you’ll want to make one just for fun the next time you go hiking?

You can make a simple lean-to shelter, or you can make something sturdier, but more complex. For example, check this amazing outdoor shelter out:

What you bring with you most likely won’t be enough. Finding food in the brush is your second biggest priority. Local knowledge of flora and fauna is essential for this task.

“A 2,000 calorie diet” is still the metric for the average person, but likely more in a survival situation due to the stress and physical exertion. A chicken breast has around 200 calories. Consider your current diet, and how much you expect you’ll need to consume in the brush.

A main consideration for what you can pack in is weight. Lightweight and space saving items are your best bet. Trail mix, protein bars, MREs are decent, but it is unlikely you will fit more than a week’s food supply in you pack along with other supplies.

You’d actually be surprised at the variety and number of lightweight foods you can pack with you:

Be conscious of what you eat now, as the cravings for sugar, caffeine, and fatty foods may be significant when there is no supply. Understand that the shift from being fat and happy to living hand to mouth is a drastic one.

My choice would be to find a supplement, such as hemp protein or whey protein, that could work as a meal substitute daily. Per 3 tablespoons you get 15 grams of protein; just mix with water.

Additionally, a large supply of a daily multivitamin to bolster your vitamin and mineral intake is a good idea. These are typically loaded with B-vitamins as well for energy, and may hold off the feeling of hunger.

In a long term wilderness scenario, with very limited food supplies, you meals will have to come from nature sooner or later. Packing some all-purpose seasoning into your mess kit would be a good idea.

Environment and climate considered, foraging should be your number one food source when trying to survive in the wild. Legitimate knowledge of edible plants versus poisonous ones should be put to the test before you find it a necessity.

I include the gathering of insects as foraging. While less appealing, insects are a clean and easy source of protein if you know what to look for. Do the research ahead of time, but maybe not the taste test.

Foraging has a better energy expended to energy gained ratio compared to hunting or trapping. Fishing is the next best option.

Some of the most common wild edibles include chicory, dandelion, elderberry, and many more.

Fishing in itself is relaxing to most, less so if you really need that fish. Rack up some alternative methods to pole fishing to keep yourself fed in the wild.

If you’re using a pole, know your fish and the bait to match. Have plenty of fishing string and spare hooks handy, even if you don’t have a pole.

Another alternative to pole fishing is fish trapping. Build a stick fortress near the shore with a little bait and only one exit, and wait for your meal to arrive. This will also allow you to hold a fresh meal, ready for when you need it. Here’s a video showing how it’s done:

Understand how to properly butcher a fish before finding it necessary. Maybe try fishing a few times too.

There are many ways to catch fish, but for bushcraft purposes, you may want to look into setting up fish traps.

If you have the skills to properly place and set a snare for small game it’s a great, low risk option. You’ve got to know how to spot a game trail, and of course how to skin and butcher without souring or wasting the meat.

A good tactic is to set two or three snares along a trail, and then return in an hour or two to check.

Here’s a video for a basic snare:

Hunting is my final resource for food, for a few reasons. It takes the most skill and uses the most resources, and depending on the size of your group you may yield more than you can consume.

If you are not a practiced hunter already, do not expect to become one while trying to survive in the wilderness outside your comfort zone. Big game should be reserved for if you are in a group of 5 or more, otherwise you will waste the animal without proper preserving skills.

Building skill with a slingshot or bow in the brush is time well spent. You will find an endless supply of ammo for a slingshot, and can take down birds and small game with it. Squirrels, ducks, rabbits, and other small game can be taken down by slingshot strikes, and are a decent source of protein.

In a bug-out or TEOTWAWKI scenario, you will want to conserve your ammunition as much as possible. Additionally, firing off rounds will only make your presence known. Hunting with a firearm, unless taking down big game, would not be how I would spend my bullet currency.

Unless you plan on dining on insects and herbs, you’ll need some cookware in your pack. I’m talking about lightweight sets like that are made for backpacking. You’ll need a suitable container for boiling water at the minimum, a 2 quart saucepan should do the trick.

Make sure you clean and fully cook wild game to avoid food illness Take care with your food waste to avoid attracting bears or scavenger animals, depending on your environment.

Cooking on an open fire will require some adjustment, so try it the next time you go hiking or camping.

Prevention will go a long way in this department also. In a SHTF scenario, and away from civilization, it will be hard to de-escalate human conflict. The safe move is to avoid it all together by avoiding humans when appropriate.

There’s going to be lots of desperate people post-collapse, some will be hungry, others will simply want to take what’s yours. And with no law enforcement to help, you’re on your own.

It is highly unadvised to bug-out without a firearm of some sorts and significant ammunition. You should also have and know how to use some alternative survival weapons such as pepper spray, an axe and your survival knife.

However violence cannot solve everything, and often too many put emphasis on their “Rambo” fantasy. Violence should be an absolute last resort, and you should hope to have your humanity intact throughout your journey.

Even with a map and compass it is possible to get lost, especially if hiking at dusk or nighttime. Learn to stay mentally present when hiking and make note of landmarks (trees, a strangely-shaped rock, waterways) as you go.

There are small breadcrumbs you can leave for yourself such as partially snapped tree branches, skewering leaves with sticks, rock stacks, or even fluorescent tape.

A good practice when you’ve set up camp is to measure out a specified distance ( say 20 paces) in a square for the sake of knowing what lies in your immediate perimeter, as well as seeing your camp from a few angles. Mark it on your GPS if you have one.

You could easily miss your camp by 20 feet and never know it if you drop your gear and wander off in search of firewood. Leaving markers that you will recognize will let you know when you enter an area you’ve been in before.

In the event of full or partial societal collapse or extreme disaster, being out of the ensuing chaos is sometimes your best bet for survival.

If times become desperate and more people take to “bugging out” also, you will likely want to stay off the radar. Meeting other like minded groups or individuals can be a gamble , but trading skills and goods are a possibility.

Depending on your location, you may be bugging out to places where individuals or groups have long been on the fringes of modern civilization, and may have adapted to a bugged out lifestyle long ago.

If you are not already acquainted with these groups or individuals, the wilderness is not the place to introduce yourself.

Set up camp far off the trail, and be discreet with your trail markers. When away from camp, camouflage or hide your gear, and keep essentials with you at all times. Always make it appear you have less supplies than you do.

Wherever you are, you have to know your area. Where are the population centers, the water sources, the wild areas? A topographical map is your best bet, one that shows all roadways as well as elevation changes and landmarks.

Consider laminating it, and marking points of interest and possible routes along it. A good GPS with backup batteries or solar backup is great, but a hardcopy is not prone to failure or vulnerable to EMP interference.

Ideally you would have hiked out to and have a working knowledge of the area you are planning to bug out to. In practice, I like to survey potential long and short-term campsites when I am out for leisurely hikes and exploring.

Make a note of the distance to water, availability of natural shelter, and visibility/exposure to potential dangers (floods, predators, looters).

A good GPS with backup batteries or solar backup is great, but printed maps not prone to failure or vulnerable to an EMP.

Knowing how to navigate with a map and compass is also essential to your wilderness survival. Do not take for granted you know how to use a map in the wilderness unless you have done it in practice. Here’s a decent explanation on compass navigation:

My dad was military. My grandfather was a cop. They served their country well. But I don’t like taking orders. I’m taking matters into my own hands so I’m not just preparing, I’m going to a friggin’ war to provide you the best of the best survival and preparedness content out there.